- Home

- Prabda Yoon

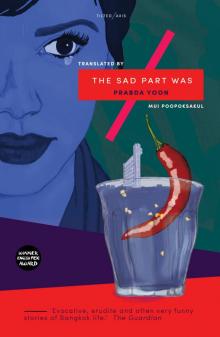

The Sad Part Was

The Sad Part Was Read online

The Sad Part was

Pen in Parentheses

The sheet of paper fell (It’s from a notebook I had when I was in seventh grade. Its blue lines are starting to fade. There’s only a single sentence on the entire page, three lines down from the top. My handwriting was neat, done with a black ballpoint pen, and the letters are still surprisingly sharp. The sentence says: “I will never change.”

Change from what, I can’t remember anymore. I’m at a loss trying to figure out whether I’ve kept my own word. I’m trying to recall what I might have been thinking when I was about twelve or thirteen; whatever it was, it seems to have been a matter of life and death. Serious enough, at least, that I’d felt the need to promise myself not to deviate from whatever path I’d been on. Whatever idea I’d managed to dream up, I must have been really taken with it.

Philosophical aphorisms used to fascinate me, perhaps because I fancied myself as a wit. Maybe I happened to read something that really struck a chord with me, and decided to make it my mantra. There was one that went: “If you want to be a good person, that means you aren’t.” I slapped my knee after I read that: Clever! Aha! That hits the nail right on the head. It’s so true: wanting something means you still haven’t achieved it. Therefore, I mustn’t want it. Instead, I have to behave in such a way that other people will consider me to be good. That one still cracks me up even now.

My mother said:

When you grow up, there might be a time when you ask yourself why you were put on this earth. When you can’t find a reason, you’ll blame your father and me for giving birth to you. ‘I never begged you to bring me into this world. The two of you made an executive decision, and I wasn’t even consulted.’ I want to tell you right now that your father and I are sorry. What you’re thinking is true. We had no right to give birth to you without asking. Not only did we bring you into this world, we boss you around, make you go to school, make you eat vegetables, make you read, make you get up, make you go to bed. We try to dictate your life. ‘You should do this for a living. You should marry that kind of person. You have to wai these people nicely when you see them. You have to respect this person, call so-and-so uncle and so-and-so aunt.’ Your father and I sincerely take the blame for all of this. If possible, when you feel like having a child of your own, ask it first if it wants to be born. If you don’t receive an answer, you can take that as a no. And if it doesn’t want to be born, don’t bring it here. Let it be born to a cat or a dog as fate will have it. Your father and I are sorry. If you’re angry or if you hate us, that’s up to you.

My mother was smart. She said those things to atone for her sins before she departed. After my parents died in a car crash, all I could do was miss them. How could I be angry at them or hate them? Just as I didn’t ask to be brought into this world, they didn’t ask to be plucked from it. At least, they wouldn’t have wanted to leave together, in the same instant. One of them must have wanted to hang around for a bit, to stay with me just a little while longer.

After the accident, my friends all worried that I would turn into a troubled kid. But that wasn’t the case at all. I may have been sad that my parents weren’t with me anymore, but I was the type that has their own universe, and it was large enough for me. The external world with parents and friends was just that – external. One or two people missing there didn’t cause my universe to crumble. Naturally, there were times when I had to emerge from my world, and that could leave me feeling sad and lonely. But it wasn’t enough of a big deal to make me turn to drugs or have suicidal thoughts. Why would I? My world had unlimited freedom. I could do anything I wanted, be anything I wanted, eat anything I wanted, have all the fun in the world without worrying about anything. If I starting taking drugs, I would distance myself from that magical world. If I committed suicide, I would never get to revel in it again.

I thought about killing myself once when I was a kid. I was feeling sorry for myself after my father wouldn’t buy me a plastic robot, even though it was way cheaper than the bottle of wine he’d just got for himself. I went and got one of his neckties from his wardrobe and looped it around my neck. In tears, I announced that I was going to hang myself. It was such a well-acted, award-worthy performance that I can still picture the scene to this day. Unperturbed, my father glanced at me briefly before walking away. After you die, he said, please don’t forget to call. I didn’t have any income of my own in those days. I didn’t even have any change in my pockets, never mind a mobile phone. Even if the other world turned out to have pay phones, placing a call would probably have been beyond me.

Pay phones don’t exist in the world of the dead, I’m sure of it now, because if they did, my parents would have called me as soon as they crossed over. I don’t think they would have baulked at the cost.

After the accident, I moved in with my maternal grandparents. By the time I was born, my father’s parents were already in the other world. My father told me that his father had been a lawyer. That was all I knew. I didn’t know anything about his mother, other than what I could deduce for myself: she was a lawyer’s wife. Once you have “wife” in your title, it doesn’t make much of a difference whether you’re a doctor’s wife, a teacher’s wife, or a janitor’s wife. At the end of the day, even a snake’s wife is there to serve her husband. No matter how tired she might be, the wife needs to have dinner ready on the table for when the snake comes home. If the snake’s muscles are stiff, the wife has to give him a massage. If the snake is thirsty, he can’t be expected to fetch water for himself.

My mother’s father ran a congee shop in the market. Her mother was unusual in that she wasn’t just a congee vendor’s wife, she was also a teacher. She taught music at an elementary school. Her taste in music was also unusual: when I woke up in the morning, I used to hear Mozart, Beethoven, Bach. My grandmother liked to listen to loud music, much to the neighbours’ annoyance. The young guy across the street was not to be shown up – he blasted out old-time rock and roll music every morning, giving my grandmother a run for her money. She would complain under her breath: What the heck is this crazy music? I only hear nonsensical screaming and yelling. There’s no artistry, no sustained harmony to please the senses. But for other people in that neighbourhood, my grandmother was the odd one out, living in a wooden house surrounded by mango trees and hanging orchids, yet listening to the light-haired farangs’ classical music. It just didn’t make any sense around here.

When he wasn’t selling congee, my grandfather was passionate about movies. He even shelled out for a 16mm projector, obtained from God knows where. Every Friday night, he sat his wife and grandson down and screened a movie of his choice. It was an important ritual for him. On a Friday when he was in a festive mood, he’d round up his friends to come spend the evening in front of the screen with us. Some of them focused on the movie; others focused on getting drunk, each to his own liking.

My grandfather’s makeshift screen was a white bedsheet stretched tightly around the edges of a door. His projector didn’t produce any sound, so my grandmother volunteered as the music director. Mozart was her eternal favourite. No matter what the movie was, the soundtrack had to be Mozart. To this day, whenever I watch a movie in a cinema, I can still hear the faint strains of Mozart echoing in my ears.

The film my grandfather screened most often was Dracula, the black and white version starring Bela Lugosi. If it was pouring outside when Friday came around, there was no need to wonder which movie he’d choose to suit the weather. Come to think of it, he even resembled Lugosi’s Count Dracula. His cheeks were sallow, his eyes were sunken, and he wore his hair combed flat to his head; his jaw narrowed sharply to the point of his chin, while his jet-black eyebrows slanted up toward his

temples. The only difference was that he didn’t have fangs, and I never spotted any tell-tale puncture wounds around the base of my grandmother’s neck. My grandfather was just an ordinary congee seller. However he was in the daytime, he stayed that way at night. He didn’t turn into a bat and start flapping around terrorising people. He didn’t get agitated and cover his face whenever he clapped eyes on a clove or two of garlic; he’d as soon as wolf it down. He was a Buddhist. He prayed to Buddha every night, right before his head hit the pillow. If someone took two long pieces of wood and arranged them into the shape of a cross, he wouldn’t have batted an eyelid. And he loved the sun. In his spare time, he liked to squat down in the front yard to trim the grass, not bothering with a hat to shield his skin from the baking heat. Whereas if he were a vampire, his body would have burned to ashes the moment he stepped out of the door.

My grandfather was human, which meant he didn’t possess eternal life. And so, one day, he died.

He used to say:

Dracula isn’t technically a ghost movie. Count Dracula is not some vengeful, disembodied spirit like those ghosts that have their guts ripped open, eyes rolled back, and tongues hanging out. He doesn’t have supernaturally long arms like a certain infamous Thai ghost that dropped a lime into the basement and was too lazy to run down and get it. Dracula is simply an unfortunate soul: he cannot die. He is cursed with eternal life, condemned to live like a beast. We ought to pity him, really. The Count might not actually want to harm anyone. He would probably be perfectly happy just living in his beautiful castle, on top of a hill in Transylvania, and minding his own business. Having to transform into a bat and go after people’s necks is probably not something that brings him joy. He can’t even go to the mall in broad daylight like other people. We are truly lucky to be able to die when our time comes. Mortality is our most valuable asset.

Nonetheless, after my grandfather proved that he, too, possessed this most valuable asset, I came to feel that immortality exists among humans as well. When someone dies, no matter who they are, they move into another person’s body, and so on in endless succession, until the last human on earth disappears.

When my grandfather died, he moved into my grandmother’s body. Every Friday she pulled out the white bedsheet and stretched it over the door, took the movie projector out of the closet and screened my grandfather’s old movies to a captive audience: me. My grandmother became a person who had two souls in one body, in charge both of projecting the movie and arranging the soundtrack.

The film she screened most often was Dracula, with Mozart as the soundtrack. She usually alternated between Violin Concerto Number 5 (the “Turkish”) and Symphony Number 41 (the “Jupiter”). These particular pieces didn’t always fit very well with the pace and mood of the movie, but my grandmother’s personal preference was always the deciding factor.

Everything proceeded as it always had, save for one person’s breathing.

I lived with my grandmother until I went to university. She never interfered with my education: Study whatever you want to study. Grandma doesn’t know a thing about it. She stopped teaching music a few years after my grandfather’s passing. The congee shop stayed in business. The taste was a little different, but the customers still packed the place out. My grandfather’s employees worked as diligently as ever, and even helped make sure that my grandmother was comfortable without becoming a burden to me. For my part, I carried on with my young and reckless life as normal.

I decided to study art because most of my friends were artists. Since I was no good at studying anything else, I acted like I was an artist, too. My drawings were pretty nonsensical, but luckily drawings with much sense in them are no longer in fashion. I used to believe that I was Picasso reincarnated. Later, I realised that even if I really were the second coming of Picasso, that wouldn’t make any difference in the long run. If Picasso was an art student today, he’d probably flunk the course. The professors would say he was stuck in the past, that his stuff was old-fashioned. Why waste time drawing strange, hideous pictures? Nowadays, it isn’t enough to just sit there sketching nudes. You have to think deep. You have to have a “concept.”

So my friends were all into concepts. All they did each day was wander beyond the school walls to scavenge for concepts. If they didn’t find any, no one complained. Inability to find a concept could be a concept in itself, so in that sense, bothering to scout around for one was a waste of time and energy.

In the four years that I spent doing art, I could count the number of concepts that I found on less than half a finger (what I did find being so lame an excuse for a concept, it didn’t deserve the full digit). I couldn’t even define the word “concept.” The whole idea was beyond me. It’s a miracle that I even found any. I was in awe of people who found a lot of them. Some students repeatedly borrowed other people’s concepts. The professors didn’t object – borrowing could be counted as a concept, too. In the end, I decided that a person’s concept was the same as their “business concern.” If other people found your “concern” interesting, you’d go places in life. If you didn’t know how to come up with your own particular “concern,” that’s, well, your concern.

In the world beyond the school fence, you couldn’t survive on your concern alone. If you wanted to make a fistful of cash, you had to put other people’s concerns first. My friends who were so darn good at concocting their concerns scattered and then dealt with other people’s – helped them sell shampoo, alcohol, chips, air-conditioners, clothes, tape, this and that, too many different things to enumerate. For some, it was a chore; for others, the more they sold, the more pride they took in their skill as sellers, which became a concept in and of itself. My grandfather was good at selling congee, but there was never any concept in it for him.

I fell into the same kind of lifestyle. As they say, when in Rome… Or as the Thai expression goes: when among the half-blind, keep one eye closed. So I went along with the others, squeezing one eye tight shut. These days, I can hardly see anymore. But I put up with it. When everyone else is busy turning a blind eye, who would notice if I managed to coax my inner Picasso out?

My friends and I graduated from an institution that happened to have alumni who were expert squinters, movers and shakers in many fields. So getting a job wasn’t difficult. Even before graduation, we got recruited to go and do this and that, so we had early training in seeing with only one eye. The day after I got my diploma, I was already hanging out at the office that swiftly became my new address. I must say, my office was a glamorous place. I felt my own importance grow bit by bit just from sitting there. People around the office looked sharp. They wore clothes that were expensive, or at least ostensibly so. Everyone’s hair was fashionably styled. Some people had perfectly good eyes – not nearsighted or farsighted or astigmatic – but still wore super thick black-rimmed glasses because that was a cool look. Geek chic, in its own way. Maybe, among the one-eyed, wearing glasses is a must. It was perfectly possible.

It turned out to hold true for me as well. I hadn’t been sitting there for more than a few months when the bridge of my nose acquired a concern of its own: supporting a pair of black-rimmed glasses. My confidence immediately shot up. Whenever anybody asked, I said my eyes had started playing tricks on me, my vision deteriorating all of a sudden. I didn’t know if I was nearsighted or farsighted, but I knew for sure that I couldn’t see very clearly. In particular, my sight was suspiciously blurry when asked to focus on the products that I was supposed to promote. I didn’t consult any doctors. I just decided to buy my own glasses. It was more of a psychological matter. When I wore them, my view of the world was clearer. It was easier to work with them on. I was better at selling. People showed respect and called me pi. For the first time, I experienced what it’s like to have someone address you as pi when you’re not their actual big brother. It put me on a high horse. My chest was mysteriously pumped up. But sometimes I had to hold those feelings in, not

flaunt them in other people’s faces. I had to feign humility, saying: There’s no need to call me pi. We’re not far off in age. But in my head I’d be saying: If you don’t fucking call me pi next time we run into each other, I’m done with you. I would always remind those in my inner circle not to rely too much on the words that came out of my mouth. My words weren’t straight, no matter which brand of ruler you used to draw the lines. It’s in the nature of those used to turning a blind eye: their visual impairment causes their brain to twist their words, too. Don’t hold it against our kind.

The first commercial that I created myself from behind my new glasses brought me moderate fame. As a welcome consequence, my social circle acquired several new nongs who practically begged to be treated as my little siblings. Another good thing that came out of it was the work that was pouring in. My work traded on humour. The more I made people laugh, the faster I advanced. I didn’t care whether the product I had to sell was in any way related to the commercial I created. Luckily, neither did the product owners. In fact, the less the commercial had to do with the product, the better. As long as the brand name stuck in people’s heads, I was on target. If you elaborated on the product’s qualities, you might end up having to lie. Why risk going to hell for something that wasn’t necessary? Just a little white lie would do, enough to create a buzz. Bees are tiny; no matter how much buzz they generate, the result remains inconsequential in the grand scale of things. When I worked, I thought of myself as a bee. But when I came up with a good sting, I was a lion.

My grandmother aged over time. I was hardly ever free to go and visit her. On the phone, she always sounded sprightly. Early every morning, she went to exercise in the park nearby with other friends her age. Whenever she had some free time, she didn’t let it go to waste. She volunteered to babysit friends’ kids and grandkids during the day, when she played her beloved classical music as lullabies for the children and herself. I knew she was strong both physically and emotionally, so there was no need for me to worry about her. But to tell you the truth, sometimes I was so preoccupied with myself that I plain forgot all about her, just eliminated her from my brain, like a dried leaf plucked off a plant. What an odd, ugly image. As if my grandmother were a shriveled leaf that no amount of sunlight could revive, a leaf that could no longer be fed, a withered leaf that ought to be trimmed off to make room for a fresh new bud. I had to remind myself constantly not to treat people like old leaves, especially my grandmother. If I tore her off, I’d be the only leaf left on the entire tree.

The Sad Part Was

The Sad Part Was