- Home

- Prabda Yoon

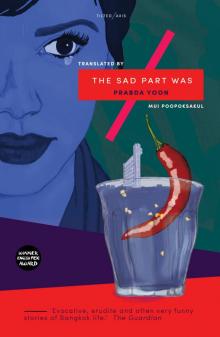

The Sad Part Was Page 2

The Sad Part Was Read online

Page 2

Some weeks ago, I got assigned to a new project. This time the product was breath mints. I was tossing ideas around in my head to see what I could dream up, and then the proverbial light bulb flicked on, as it does each time I crack a problem at work. I should point out that when I’m not thinking about work, no light bulb ever appears above my head. This must mean that my brain is otherwise dark and cloudy – it just blindly feels its way around and lets random thoughts wander. To find light each time, there’s got to be a condition attached. If it’s not for work or money, it just stays in the dark. The fear is, if the light’s too bright, it might illuminate a shockingly hollow space. The repository of my brain might appear large from the outside, as if it contained an enormous supply of intelligence, but if a bright light bulb were shining in there all the time, you’d see an empty warehouse, pin-drop quiet. Better just to leave it in the dark.

This time, though, the lightbulb above my head illuminated the face of Bela Lugosi, made up as he is in the Dracula movie. That’s it: I would find a guy with a pointy chin and have him dressed up to look like the Count. A mature actor past his prime would be best, someone who was having trouble landing any film or TV roles. I could chalk it up as an act of charity. Maybe the actor would make a comeback off the back of my commercial. Then I would become known as a savior who can bring the dead back to life, a person of great abilities. In the land of the one-eyed, age commands respect, even in a person who’d been consigned to the scrap heap only a few years earlier.

After I found my Count, I would need a model to play the unfortunate victim. A fresh-faced girl would be best, not one who’s been made up for so many cameras that her pores have become clogged and her skin pimpled. That kind are all pop singers by now, anyway. It was too much fuss and too much money to secure them for a commercial. The best solution would be just to pick someone off the street. If the girl got lucky, her career might explode, and within a few months she might have turned into the next It Girl. And the luck wouldn’t all be one way; if she was into older guys, I could take advantage of having introduced her to the industry and acquire some barely-legal arm candy, if only for a few months. Once I’d found a female model to my liking, I would need a handsome male model to play the vampire slayer. The client would be happiest with someone already fairly famous. For me, it didn’t matter either way. I wasn’t after a handsome male model to hang on my arm. Let the gay guys on the team decide.

My commercial would have to be black and white, like the original film. The title would be in that Gothic-looking font often used for the opening credits of horror flicks. I would have huge letters reading, “Dracula Meets …” (The ellipsis was the brand name of the breath mint.) The first shot would be the Count’s stone castle, perched on top of a hill. There’s a torrential downpour. Lightning strikes with hair-raising flashes. From there we cut to the interior of the castle. Things are heating up between Dracula and the female victim, reclining on his bed. Then a close-up of the sharp tip of his fang moving in on the pale, smooth skin of her neck.

Suddenly, the Count hears the castle door being knocked down. Caught off guard, he pauses before he can sink his teeth into the young woman’s neck and satisfy his craving. Cut to the bottom of the staircase on the ground floor of the castle, where the strapping young vampire slayer is mounting the stairs one at a time, a flaming torch in his left hand and a cross in his right. The Count appears out of nowhere at the top of the staircase. His face is boiling with rage. The young man doesn’t hesitate. He throws the torch at Dracula, hoping to burn the vampire into submission. But the Count is a former kick volleyball player. Just one bounce off his head and the torch is deflected back onto the young slayer, who struggles to put out the fire burning his clothes. But the young man doesn’t back down. Even though his hair is burnt to a crisp, he is determined to defeat the demon. Holding the cross up in front of him, he inches closer to the Count, but Dracula stands his ground, completely unfazed by the holy symbol. He even smirks, making a mockery of the young warrior. The handsome young man is genuinely baffled. Dracula abruptly takes pity on him and decides to reveal his secret. He gestures for the young man to turn around and look at the castle wall.

The camera pans to where the Count is pointing. Not far from the scene of their showdown, a shrine of Buddha images comes into view, complete with candles, incense and lotus flowers. Dracula has changed religion. Even a truck full of crosses would be of no use. Mortified, the young man breaks into a sweat and throws the cross aside. He puts his palms in prayer to wai the Count before bolting down the stairs and out of the castle gate. The scene cuts back to the Count’s bedroom. The female victim is still lying motionless on the soft mattress. Dracula enters the room with a smile, ready to resume his attack. Cut to a close-up of the Count’s fang once again. This time, when the sharp tip is about to graze her pale skin, the beautiful young woman opens her eyes and hands the vampire a breath mint. “If you don’t suck on … you can’t suck on me.” (The ellipsis, again, being the brand name of the aforementioned breath mint.) And then she smiles sweetly. Dracula submissively pops the breath mint in his mouth.

The last shot is back outside the castle. The rain has stopped. It’s becoming light out. Two bats fly out from the second-floor window, flapping jauntily side by side. The accompanying voice-over says, “The modern Dracula takes …” (Ellipsis, breath mint.) After the two love-bats disappear offscreen, the words “Stay tuned for part two” appear – just in case this commercial of mine turned out to be a hit and the client commissioned me for a follow-up. If not, it didn’t matter; it would still look cool, anyway.

The soundtrack would be sure to feature Mozart, but only as a faint background to the action. The main music would be the kind of formulaic stuff typical of horror movies, because in truth, Violin Concerto Number 5 and Symphony Number 41 didn’t really chime with the content. But since I was selling my childhood memory, I might as well recreate it as closely as possible.

As I had guessed, my idea was well-received by the others in the office. I cooked it up for people to like, so it’s natural that they did. That’s what I do. It got the green light after just two meetings. We could start shooting right away.

They say we humans use only a tiny fraction of our brains. Those genius types might manage a little more than ordinary folks. But I’m no genius. The more I think, the smaller the fraction of my brain I use. And the bosses use an even smaller fraction than I do. Otherwise they wouldn’t take to my shallow ideas so readily. Whatever I come up with leaves them in stitches. The lamer the idea, the louder they laugh.

The exploitation of my childhood memory was a success. The girl who played Dracula’s victim didn’t become my arm-candy, but I did get a round-eyed intern to take in the nightlife with me. We went sightseeing everywhere there was to see, after which there was no more seeing to be done, not even of each other. I have to start saving again to prepare for new sightseeing adventures with a new girl. Right now, I don’t know who she’s going to be, but that’s nothing to get worked up about.

The Dracula Meets the Breath Mint commercial was a source of considerable pride for me. I even recorded it for my grandmother to watch when she got lonely.

I delivered the Dracula videotape to her in person, in a new car earned with my own blood, sweat, and tears. I had to have something to show off to drag myself over there. My grandmother was so happy. She spent the whole morning preparing my favorite foods so she could spoil me. I didn’t waste a second when I got there. Grandma, I told her, look at this first. I don’t know if you’ve already seen it on TV. I made this commercial especially for you and Grandpa. I pushed the videotape into the player. Excited, my grandmother waited eagerly for the picture to appear on the screen. But her screen wasn’t the one on the TV. Her eyes were fixed on me, on my face, as if I were an old movie she hadn’t seen in a long time. I pretended not to notice. I was busy mouthing off, giving her the behind-the-scenes story of the making of the co

mmercial, not paying attention to whether or not she understood the advertising jargon. My grandmother didn’t seem to mind either. She just sat and listened, eager and obedient. She smiled at whatever I said. When I laughed, she laughed. If all of my clients were like her, life would be great. Work would be so much easier.

My grandmother watched my Dracula Meets the Breath Mint commercial with a smile. But I felt strange watching it with her in her house, the setting of my memory of the blood-sucking Count, the memory that had earned me money to spend, that had bought me the vote of confidence from colleagues and clients. I stared absentmindedly at my grandmother’s ancient television set.

It’s good, son, was her comment after the movie ended.

It’s no good.

I asked if she heard the Mozart in the movie. She looked surprised: Was Mozart in there? I nodded: Yes, the “Turkish” and the “Jupiter”, the ones you always played as the soundtrack for Dracula. The one with Bela Lugosi, that Grandpa used to screen on Friday nights. She said: Oh yeah? Really? Was it there? I didn’t hear it. I’m old, sweetheart. My hearing’s not what it was. I wanted to rewind the tape and show the movie to her again: Grandma, listen closely. She said: There’s no need. I believe that Mozart is in there, just like you said. We don’t have to watch it again.

Today I’m at my grandmother’s house, but she is no longer here. I don’t know where she’s gone, just as I don’t know where my parents have gone, or where my grandfather’s gone. I came to my grandmother’s house to pack up. Since my grandmother is no longer here, the house is no longer necessary. I came to go through the stuff and pick out anything I want to keep. I’m only realising now that my grandmother was quite the hoarder: school books, cartoons, magazines, toys, stuff from my childhood. She kept all of them neatly arranged in the cupboards. I probably can’t take them all today.

There are dozens of boxes of my grandmother’s classical music records, every one of them still in good condition. My grandfather’s movie projector, too, is shiny as new. All of his movies are still in their metal cases. I held one of them in my hand for longer than the rest. The case was labelled “Dracula”, in English, in my grandfather’s handwriting. I thought of that white bedsheet and the beam of light from the projector, how it used to cut a line through the darkness on its way to the white fabric.

I flipped through several high school notebooks and textbooks with outdated-looking covers. They were full of doodles that I’d done surreptitiously during class. Many pages of the notebooks were smeared with Star Wars. I haven’t played Star Wars in ages. It’s a kid’s game. You draw an army of stars and then you shoot a line with the tip of a ballpoint pen to try and hit the other player’s army. Any star you hit gets blacked out.

I remember how I made several attempts to keep a diary, but got tired of it and gave up in less than a week each time.

What’s there to record from a day in the life of a child, anyway? Today I woke up and went to school. I got spanked by the teacher. I came home, watched TV, read some comics, went to bed.

The sheet of paper with the faded blue lines is a page from one of the diaries I didn’t finish.

“I will never change.”

Change from what, I can’t remember anymore.

But I want to keep it. Maybe I’ll remember one day.), so I bent down and picked it up.

Ei Ploang

I don’t have all that much to be proud of, but one memory that still makes me smile to this day is Ei Ploang calling me a good person.

I used to address him more politely as Khun Ploang; the bold switch to Ei is only a recent development, and one I never would have had the audacity to make without the express permission of the man himself.

One morning in Lumpini Park, Ei Ploang handed me a scrap of paper. “You can call me ‘Ei’ from now on,” he said, “Here’s a letter of certification.” It even had a signature.

I opened the letter:

On the 17th of August 1999, I, Mr. Theppitak Rakakart (nickname Ploang), came, by destiny, to meet a young Thai man by the name of Praj Preungtham, a third-year university student. Mr. Praj and I hit it off from the aforementioned date and have since shared the pleasure of many conversations. Consequently, a close friendship has developed. Nearly a year has now elapsed; our friendship remains firm, and is forecast to flourish further in the future, a welcome surprise. Notwithstanding my seniority in age (a matter of a full five years) I hereby grant Mr. Praj Preungtham official permission to append the crude prefix “Ei” to either my first name or nickname, whenever the use of either such is necessary. I swear not to take offense at his addressing me in such a manner. Furthermore, if Mr. Praj does not consider me a close enough friend for us to be on “Ei” terms, I shall terminate the friendship and shall wish upon him a restless death without the possibility of reincarnation. I certify by my honour that the words in this letter reflect my true intentions.

Signed,

Theppitak Rakakart (Ploang)

[Ei Ploang’s squiggly signature appeared under his neatly written name]

Back when Ei Ploang was still Khun Ploang to me, his entire body seemed to radiate an aura. He just had to sit there, and it would appear as if a universe revolved around him. It made you wary of approaching him; for fear a meteorite might strike you down. His eyes appeared to house molten volcanoes, or brewing storms, or whirling tsunamis, or high-voltage electricity exploding in a short-circuit, or those damned downpours that dump their loads on you then proceed to dribble for the next couple of hours, or black holes ready to swallow up time, or evil spirits lying in wait to prey on a wandering soul.

I had to wait until he closed his eyes before I had the guts to go over and say hello.

“Are you sleeping?” I asked, gingerly lowering myself onto the same bench.

“Just resting my eyes.” Ei Ploang answered promptly and clearly, without bothering to actually open his eyes and examine his questioner.

In those days I regularly woke up early to go jogging in Lumpini Park. School was out, and as my internship hadn’t started yet, I wanted to find a productive outlet for my nervous energy. Jogging in the park was a popular past-time, and apparently just as beneficial for your physical health as for your mental well-being. So I thought I’d try the trend myself and give the sportswear stuffed at the bottom of my wardrobe an airing in the light of day.

The first morning I stepped inside Lumpini Park, it isn’t strictly accurate to say that I went jogging. Let’s just call it a reconnoitre before the actual expedition. When I first arrived, I was stunned by the sheer number of those engaging in exercise, which far exceeded my expectation. I strolled around and, when I got tired, stopped to take in the birds and trees, the dogs and cats and ants, the way animal lovers do. Once I’d had my fill of the various flora and fauna, I resumed walking. That morning, I never even broke into a run.

As I became a frequent visitor to the park, my leg muscles started of their own accord to yearn for stimulation. Soon I was one of those runners, floating along to the beat of hundreds or thousands of human hearts, moving in tandem like ants in a colony. But we weren’t worker ants. We didn’t run in single file, intent on the survival of the majority. We didn’t carry food on our backs to distribute later. We ran for personal reasons, some for fitness, some for vanity, some to reduce stress, and some to ease loneliness.

Then we all went our separate ways.

I’d seen Ei Ploang several times before I decided to stick my nose in and chat him up. Ei Ploang never ran; he never even got up to stretch. He just sat there scanning his surroundings with his mysterious eyes, as if looking for someone he knew. As far as I could tell, no such acquaintance ever presented themselves. Or else, nobody ever dared claim acquaintance with him.

Some days he chose to sit by the pond, staring blankly at the ducks and geese and turtles and fish that surfaced every now and then in search of scraps of food. As far I could t

ell, none of these ducks, geese, turtles or fish were his especial acquaintance, either. But Ei Ploang always showed up, as if he was sure that one day he would find what he was searching for.

Ei Ploang was, without doubt, a good-looking guy. His eyes were big and round. His reddish-brown skin was smooth in the morning sun. His dark brown hair was razored short on the sides all the way around, sort of like a crew cut. It was plain to see that he didn’t come to Lumpini Park to exercise. He usually wore a white shirt and khaki trousers. Some days he was even more smartly dressed, even going so far as to wear a tie.

When Ei Ploang opened his eyes, I was confronted with a pair of huge pupils staring at my face. They remained fixed on it for several seconds, to the point that I was afraid I would fall into their twin black holes and be devoured.

“Oh, it’s you. You come jogging here every day.”

“You’ve seen me?” I asked, even though I knew the answer.

“Several times.”

“I’ve noticed you myself. You often sit here, but you never go for a run.”

“That’s because I don’t come here to run.” When he finished his sentence, his gaze shifted to a new target. Mine followed his out of curiosity.

His new mark was a chubby woman jouncing along the path. A little girl with braids was trailing close behind her.

The Sad Part Was

The Sad Part Was