- Home

- Prabda Yoon

The Sad Part Was Page 11

The Sad Part Was Read online

Page 11

The sad part was, June wasn’t in love with any of our crew, which was probably why she felt at ease hanging out and partying with us.

It took me a fairly long time to come to terms with that fact. We all needed quite some period of adjustment before we were able to have fun, messing around with one another at the crying parties.

—

“What? A crying party?” Lert had been baffled at first, when I spoke to him on the phone earlier in the week. I’d contacted the building to ask who’d moved into June’s apartment. The employee who answered the phone put me through to Lert, I introduced myself and told him about June.

“Oh, the woman who killed herself in this apartment?” Lert’s voice was so flat it was as if he was talking about somebody crossing the street when the cars had stopped at the red light – oh yeah, her, the person crossing the street.

Yes, that was June. I continued by telling him that three friends and I had a favour to ask. We wanted to use his place to throw one final crying party. We were prepared to let him do background checks and look at our national IDs, or to provide any supporting evidence that would make him trust in our good intentions. We were happy to let him stay behind and act as our chaperone, or even join in with the party, if that was what he wanted. It was all fine by us.

“You all met up here every Sunday to get drunk and eat raw bird’s eye chilies until tears came out of your eyes? And you competed to see who could cry the longest and the most? That sounds ridiculous… and kind of awful,” Lert opined after I’d finished explaining the gist of the crying parties to him.

He seemed to have a good grasp of it.

—

It’s probably no great revelation to say that June was the one who instigated the crying parties. As I understood it, she founded them on a day when she was dealing with some form of heartache. But June didn’t breathe a word of this to us – she even acted particularly cheery when she opened the door to welcome us to the first gathering. As time passed, we gradually uncovered for ourselves that the crying parties weren’t organised merely for our entertainment; rather, June used them as a way to detach crying from sadness.

She wanted to train herself to cry for amusement.

The four of us began to fathom June’s behaviour not long after the crying parties began, but we didn’t care. Getting to have these special moments with her every week meant far more to us than whatever private motive she might be harbouring.

Before we knocked on June’s door, the four of us would go pick up the provisions together. The selection of the chilies was no less crucial a step than chomping them down. Only rarely can anyone have picked out chilies as meticulously and painstakingly as we did. The vendors would regard us with question marks in their eyes.

“I’m not sure…” Lert said into the receiver. “Why should I let four male strangers use my place as a venue for chili worship?”

I proposed that we pay him, as if we were renting his room for a few hours.

He accepted, under the condition that he would stay in to monitor our conduct.

Hence we were here, now, Sunday evening, around half past seven.

Lert had inherited some of June’s furniture, that her family had abandoned there. Along with the hideous green rug, her grey sofa and coffee table were just as we remembered them. I didn’t know if the landlord had notified Lert of the history of the stuff in the room. Did he know that June’s heart had stopped beating on that sofa?

Num was the first to lower himself down onto it. He stared blankly at us, and then Tae walked over to sit next to him. The sofa wasn’t large enough to accommodate four people comfortably, so Oh and I sat down on the carpet. I placed a yellow plastic bag stuffed with red and green chilies on the table in front of us that had Lert’s computer magazines strewn all over it. As soon as Oh set the bag of beers down, Tae reached in for a can.

We each felt parched.

Lert had his eye on us as though he were expecting something shady. He stood stiff as a statue in front of the TV in the corner of the room. “You guys are going to sit and drink beer and eat chilies until you cry, and then you’re going to leave – right?” Lert asked, stepping a little closer to us.

We nodded in unison. I pointed at the chili bag and asked, “You want some?”

“No, thanks.”

“We won’t stick around long,” Tae told him, taking a sip of his beer. “We’ll probably wrap things up by nine.”

“I hope so,” Lert said. He looked concerned, and also like he didn’t know what to do with himself. It was as though the room belonged to us again – no, not to us, to June.

“I don’t know how I agreed to let you all come here,” Lert said. “I think this whole operation’s too wacky by far.”

The four of us looked at each other. Num reached inside the bag of chilies, extracted a bright red specimen and bit half of it straight off.

The crying party was thereby officially in session.

“You should join in,” I encouraged Lert. I was trying to find a way to help him relax, both mentally and physically. “The release of tears without sorrow or pain is a really interesting sensation.”

“Interesting? I think you’re all demented.” Lert refused to loosen up.

“I’ve changed my mind. It’s making me uneasy, having a bunch of strangers sitting around in my room. I have to ask you all to leave right now.” I heard the quiver in his voice. It seemed he’d had to summon a good deal of courage before he could open his mouth to kick us out – in his eyes, chili eaters must have been mighty intimidating.

“We can’t leave yet,” Tae said sluggishly, completely unperturbed. “The party’s just started. Don’t worry, we’re good guys. We’re harmless. We just want to finish our party, and then we’ll go. In the meantime, feel free to do your own thing.”

“But this is my apartment! I have the right to kick you out. Please pack up and leave, or else I’m going to have to call security,” Lert raised his voice more. His face slowly turned red. I sensed that he genuinely wanted to call security.

We looked at one another again. Oh and Num’s cheeks were already drenched with tears. Apparently they’d gobbled the chilies down in a hurry. Meanwhile, Tae’s tears were welling up, and I myself was starting to feel the power of the spiciness build up inside my nose – I’d eaten only a single chili, but, as I had the weakest tongue in the group, I was sure to start crying soon.

—

“I said get out of here! Didn’t you hear me?” Lert was really becoming a nuisance. We consulted with each other in silence. Four pairs of soggy eyes posed the question: How are we going to shut this idiot up?

When he saw that no one was heeding his order, Lert walked straight over to the white phone hanging on the wall next to the kitchen area. “I’m calling security up here right now,” he threatened.

“Hey now… cool off a little, won’t you? You can see that we’re not doing anything bad. We’re just sitting here eating chilies, for fun,” Num said. The voice that came out of him sounded distinctly like a snivel.

“Go eat them somewhere else,” Lert argued.

“But this is the only place where our crying parties can happen,” Num explained. His words were becoming increasingly difficult to decipher. “And we paid you the rent as agreed.”

“I don’t want your money anymore. I just want you all to leave my apartment, right now!” Lert picked up the receiver.

—

I was crying.

I sipped my beer and looked around the room through the veil of tears. Then I tilted my head down and stared at the stains of memories on the surface of the rug. My tongue felt swollen and numb. The others were probably experiencing similar symptoms. Each of us scanned the room, in search of June’s eyes.

“Security’s on the way up,” Lert said, with the bold voice of a winner.

We went on sittin

g there in silence, continuing to eat the chilies.

The four of us weren’t exactly dear friends. We were starting to realise only now that we hadn’t actually wanted to come here – but we would stay and cry until we were dragged out of the room.

We were waiting.

Waiting in the same room that was no longer the same.

We tried searching for June in our good-time tears.

But we didn’t find her.

We only found that our tears weren’t tears of amusement.

Found

“He’s disappeared,” Duan hollered, her voice nearly swallowed up by the sound of the waves.

“But he promised,” I yelled back, feeling irritated. Duan nodded in agreement. Then she stamped her way further along the beach, still hoping to find the middle-aged fisherman.

Dusk was approaching. Everyone on the beach was awaiting the special night. Tomorrow, the people of the world would wake to greet the final year of the twentieth century. Even though it was none of Buddhists’ business, our nation got caught up in the excitement along with everybody else. Duan and I were planning to celebrate midnight out on the ocean. The owner of a fisherman’s boat had promised to take us out to sea so we could lie back and gaze at the stars.

I watched Duan pace further off, then turned to look at the waves as their crests appeared on the surface.

Nearby, a boy with a buzz cut was walking in a circle, his face turned toward the sand.

I strolled over to him, thinking I could strike up a conversation and kill some time.

“What are you doing, kid?”

The boy didn’t bother to look up. He continued his relentless circles.

“Looking for something.”

“Did you lose something, kid? What is it? Do you want me to help you look?” I gazed at the crown of the little boy’s head, finding it endearing. Children’s crowns always seemed somehow precious to me, while those of adults were strangely pathetic.

The boy didn’t answer. His concentration remained glued to the surface of the beach.

“Did you lose it here?” He nodded.

“What is it? So I can help you look.”

He raised his right hand and pinched his thumb and index finger together, forming a single tip; his lips were still sealed tight.

I could only guess that the object was diminutive. I began to sweep the ground with my gaze. Near my left foot was a soda cap, concealed among the grains of sand. I bent down to pick it up.

“Is this it?” The boy tilted his head up and looked at the object in my hand for a millisecond before shaking his head.

No other foreign object was in the vicinity.

—

Is the world going to end tomorrow? It doesn’t appear so. It would be odd if it blew up into smithereens all of a sudden. Sorn said:

The world isn’t going to end. The farangs are being insane. It’s just superstitious nonsense, whatever prophesy the religious fanatics believe. In the course of history, who knows how many times deranged people have predicted that the world was going to end, and it hasn’t ended yet. But if it does, so be it; it might even be beautiful.

But come to think of it, it probably wouldn’t be too good. There’s still so many things I want to do. I want to travel around the world. I want to go to Europe. I want to go to the U.S. I want to go China. Especially China. I want to bless my eyes with the sight of the Great Wall, just once in my life. All the Wonders of the World, I want to see them all. I want to see the pyramids. And India. And Nepal.

I want to go stand somewhere elevated; it doesn’t matter how far above the sea. Somewhere where my ears would go numb, my legs would stiffen, my heart would beat like the engine of a train as it pulls into the platform, slow but deliberate, rhythmic but purposeful.

A place that can make my eyes sting and tear, but where the liquid that wells up infuses the image before me with a dream-like quality.

I want to look down at the earth, and not rub elbows with it any longer.

I want to be above the world, higher than the reach of life’s banality, higher than the cyclical chaos that follows the trajectory of traffic, higher than skyscrapers, higher than democracy, higher than the calories in a chocolate bar, higher than Einstein’s IQ, higher than the cost of living in developed countries.

In a place that hasn’t been developed and doesn’t want to be.

A place where I’ll be cold, but where at least I’ll know that I’m cold, without having to rely on anyone else’s opinion.

I won’t have to find out from the Government Spokesperson’s announcement. I won’t have to listen to the Weather Authority’s forecast. My senses won’t have to be awakened by department store sales on sweaters and jackets.

A place where I’ll know it’s cold without relying on language.

A place where I’ll know we’re cold because my bones tell me so.

If I don’t believe in my bones, how could I go on standing?

There in that place, I’d keep standing until my life is no more.

Until my life is no more.

If the world snatched the chance to end first, how could I get to go to such a place? Sorn said:

The world’s not going to end tomorrow. Don’t worry.

That’s what I think, too.

Where did that fisherman disappear to? He promised he’d be waiting for us. If we can’t find him, there goes our chance to go star-gazing out on the open sea. We’ll have to come up with another plan for our New Year’s celebration. Sorn would probably be disappointed. We had our hearts set on listening to the sound of the waves, just the two of us. Hmm, but with the fisherman, that would make three.

Mr. Fisherman, oh, where are you? It’s almost sundown.

—

“If you don’t tell me what you’re looking for, I can’t help you look.”

The boy was still keeping mum.

“Is it a toy?” I persisted.

The boy shook his head. He furrowed his eyebrows, bringing them close together. I stopped staring down at the sand. The light was beginning to dim. In the dark blue sky, the faint white outline of the moon appeared.

The beachside road was lined with buildings, from low structures to high-rise condominiums, from one-star to two-, three- and four-star hotels. Each establishment was preparing for the night’s celebration, to send off the old year and welcome the new. A barrage of fireworks would explode in the sky. Hundreds of paper lanterns would float up, enough to compete with the stars. Even though people on the beach were still preoccupied with their own or family activities, there was no one who didn’t feel the approach of the crucial second.

Or perhaps this small child didn’t?

“Do you know what tomorrow is, kid?” I asked, becoming genuinely interested in guessing what he was searching for.

The boy regarded me seriously for the first time.

“Of course.” His voice showed a hint of aggravation, as if to say, I may be a child, but I’m not altogether clueless – how could he not know the significance of tomorrow?

“What is it, then?” I kept teasing him, being annoying on purpose.

“New Year’s.” The boy went back to examining the sand.

“And do you know how this New Year’s is more special than other New Year’s?”

He paused to think for a moment.

“The world’s gonna end,” he said with confidence.

I laughed in my throat, as an indication that I found his answer cute.

“Is that what you believe? That the world’s going to end?”

The boy nodded in earnest.

“And doesn’t it scare you?”

He shook his head even more earnestly than he had nodded.

“Why not?”

“Why should I be scared?” The boy crouched down close to the sand.

His right hand dug into the fine grains, created by centuries of erosion on the part of the ocean’s water. He used all five fingers to squeeze and knead the sand for a while, and then he flung it aside. His little child’s hands were still empty. No object had been found.

“Well, wouldn’t it be scary if the world ends? Everyone would die. Your parents would die. I’d die. You yourself would die. It’s scary.”

“Ugh…” The boy exclaimed, visibly annoyed. He stood straight up again and rubbed his palms together, brushing off the sand that clung to the skin.

“…dying is just the blink of an eye.”

From a distance, Duan waved to me. Next to her, I could make out the figure of the fisherman who was to take us out to sea on his boat that night.

To die.

In the blink of an eye.

Translator’s Afterword

In 2002, you couldn’t be Thai and call yourself a reader without knowing the name Prabda Yoon. Having just won the S.E.A. Write Award for Kwam Na Ja Pen (the collection from which most of the stories here have been taken), the author was being hailed as the voice of a new generation, of those Thais whose collective consciousness is tied to the experience of growing up in a fast-urbanising country.

Prabda and I are both children of ’80s Bangkok, old enough to remember the city without a sky train or a McDonald’s, but young enough for these signs of modernisation not to seem out of place when we imagine our hometown. The ’80s and ’90s were comparatively light-hearted decades in Thailand, with economic realities becoming easier and, for better or worse, politics regarded with relative apathy.

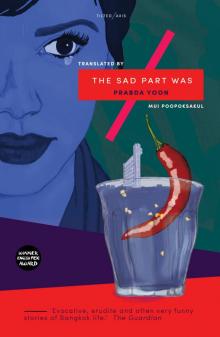

The Sad Part Was

The Sad Part Was